In this article, I want to walk you through the Pressure Belts Of The Earth i.e. World Atmospheric Pressure Distribution on Earth, Coriolis Effect, and Atmospheric circulation (Hadley, Ferrel, Polar Cell) for UPSC Examination.

Pressure Belts Of The Earth

Pressure –

- A column of air exerts weight in terms of pressure on the surface of the earth.

- The weight of the column of air at a given place and time is called air pressure or atmospheric pressure.

- Atmospheric pressure is measured by an instrument called a barometer.

- Atmospheric pressure is measured as force per unit area. The unit used for measuring pressure is called millibar.

- One millibar is equal to the force of nearly one gram per square centimeter.

Factors Controlling Pressure Systems –

There are two main causes, thermal and dynamic, for the pressure differences resulting in high and low-pressure systems.

Thermal Factors –

- When air is heated, it expands and, hence, its density decreases. This naturally leads to low pressure. On the contrary, cooling results in contraction. This increases the density and thus leads to high pressure.

- Formation of equatorial low and polar highs are examples of thermal lows and thermal highs, respectively.

Dynamic Factors

- Apart from variations of temperature, the formation of pressure belts may be explained by dynamic controls arising out of pressure gradient forces and rotation of the earth (Coriolis force).

What is Pressure Gradient?

- The rate of change of atmospheric pressure between two points on the earth’s surface is called the pressure gradient.

- On the weather chart, this is indicated by the spacing of isobars.

- Close spacing of isobars indicates a strong pressure gradient, while wide spacing suggests a weak gradient.

Vertical Distribution

- The columnar distribution of atmospheric pressure is known as the vertical distribution of pressure.

- The mass of air above in the column of air compresses the air under it hence its lower layers are denser than the upper layers; As a result, the lower layers of the atmosphere have higher density, hence, exert more pressure.

- Conversely, the higher layers are less compressed and, hence, they have low density and low pressure.

- The temperature of the air, the amount of water vapor present in the air, and the gravitational pull of the earth determine the air pressure of a given place and at a given time.

- Since these factors are variable with a change in height, there is a variation in the rate of decrease in air pressure with an increase in altitude.

- Rising pressure indicates fine, settled weather while falling pressure indicates unstable and cloudy weather.

Horizontal Distribution

The factors responsible for variation in the horizontal distribution of pressure are as follows:

- Air temperature – Equator Polar regions

- The earth’s rotation – Coriolis force

- Presence of water vapor – Inversely related to pressure

Air Temperature

- Earth is not heated uniformly because of unequal distribution of insolation, differential heating and cooling of land and water surfaces

- Air pressure is low in equatorial regions and it is higher in polar regions.

- Low air pressure in equatorial regions is due to the fact that hot air ascends there with a gradual decrease in temperature causing thinness of air on the surface.

- In the polar region, cold air is very dense hence it descends, and pressure increases.

The Earth’s Rotation

- The earth’s rotation generates centrifugal force.

- This results in the deflection of air from its original place, causing a decrease of pressure.

- The low-pressure belts of the subpolar regions and the high-pressure belts of the sub-tropical regions are created as a result of the earth’s rotation.

Presence of Water Vapour

- Air with a higher quantity of water vapor has lower pressure and that with a lower quantity of water vapor has higher pressure.

World Pressure Belts

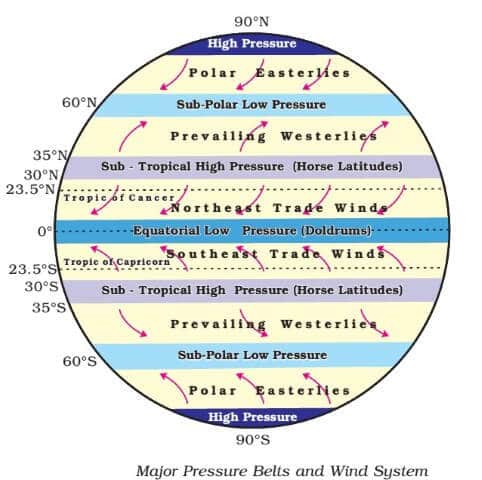

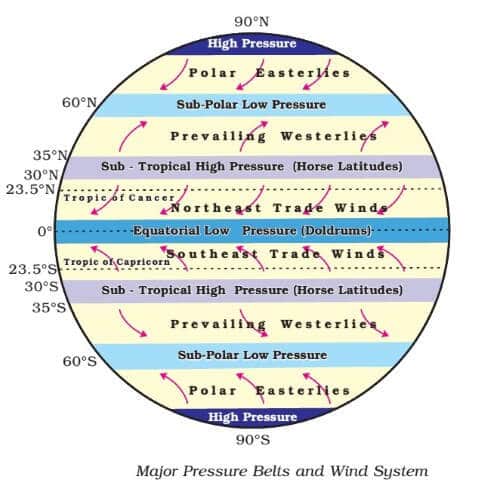

On the earth’s surface, there are seven pressure belts. They are –

- Equatorial Low

- The two Sub-tropical Highs

- The two Sub-polar Lows

- The two Polar Highs.

Except for the Equatorial low, the others form matching pairs in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres.

Equatorial Low Pressure Belts

- This low-pressure belt extends from 0 to 5° North and South of the Equator.

- Due to the vertical rays of the sun here, there is intense heating. The air, therefore, expands and rises as convection current causing low pressure to develop here.

- This low-pressure belt is also called as doldrums because it is a zone of total calm without any breeze.

Sub-tropical High Pressure Belts

- At about 30°North and South of the Equator lies the area where the ascending equatorial air currents descend. This area is thus an area of high pressure.

- It is also called as the Horse latitude.

- Winds always blow from high pressure to low pressure.

- So the winds from the subtropical region blow towards the Equator as Trade winds and another wind blow towards Sub-Polar Low-Pressure as Westerlies.

Circum-polar Low Pressure Belts

- These belts located between 60° and 70° in each hemisphere are known as Circum-polar Low-Pressure Belts.

- In the Sub-tropical region, the descending air gets divided into two parts.

- One part blows towards the Equatorial Low-Pressure Belt. The other part blows towards the Circum-polar Low-Pressure Belt.

- This zone is marked by the ascent of warm Sub-tropical air over cold polar air blowing from poles. Due to earth’s rotation, the winds surrounding the Polar region blow towards the Equator.

- Centrifugal forces operating in this region create the low-pressure belt appropriately called Circum-polar Low-Pressure Belt.

- This region is marked by violent storms in winter.

Polar High Pressure Areas

- At the North and South Poles, between 70° to 90° North and South, the temperatures are always extremely low.

- The cold descending air gives rise to high pressures over the Poles.

- These areas of Polar high pressure are known as the Polar Highs.

- These regions are characterized by permanent IceCaps.

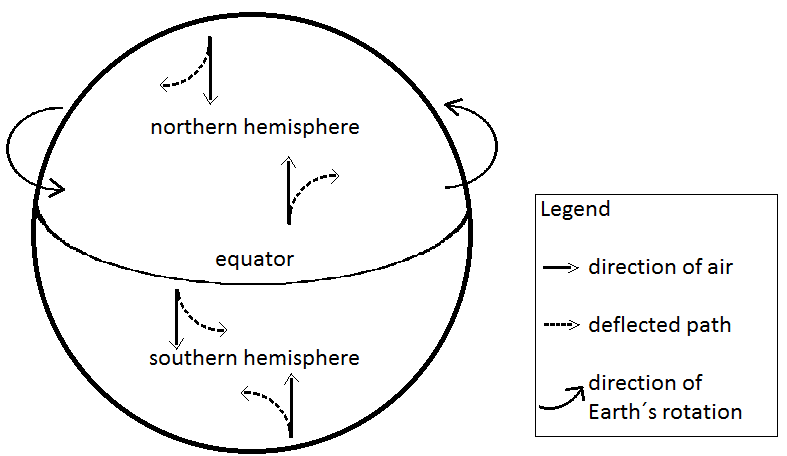

The Coriolis Effect

- The Coriolis deflection sets the major constraint on how many cells the atmosphere of a planet divides into. Coriolis force is stronger for more rapid rotation. It is the size of the planet and speed of rotation (and a lesser extent, the depth of the atmosphere) which determines how many of these. Earth’s atmosphere divides into 3 cells.

- For Jupiter, it is many more, as it is 12 times larger in diameter and yet has a day only 12 hrs long. Coriolis Force is very strong.

Atmospheric circulation

Atmospheric circulation is the large-scale movement of air and together with ocean circulation is the means by which thermal energy is redistributed on the surface of the Earth

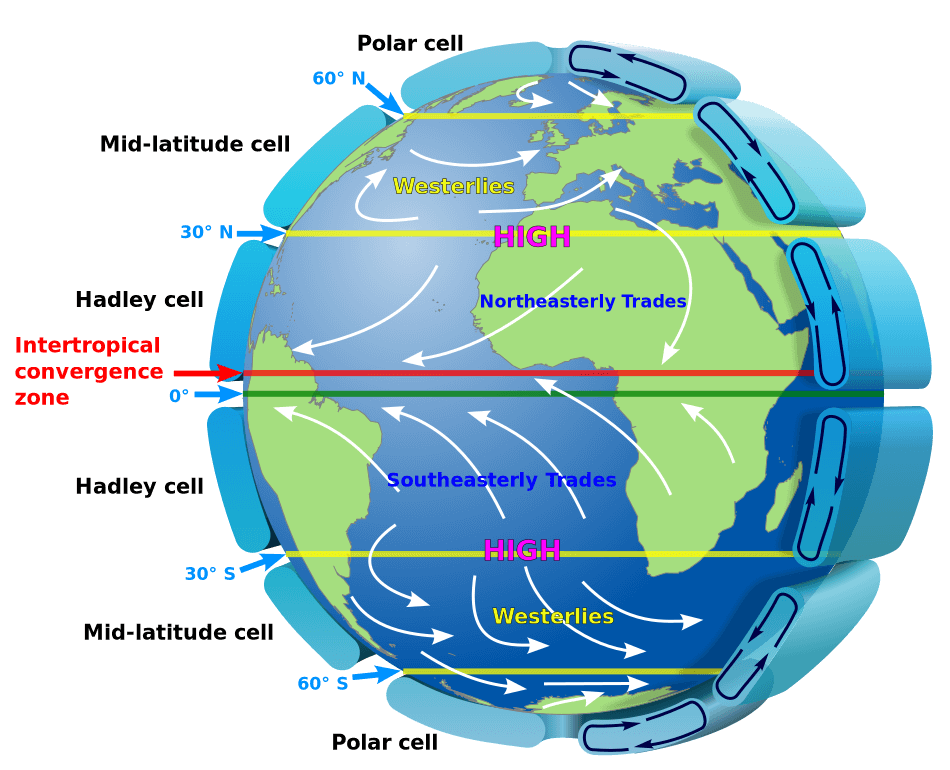

Latitudinal circulation – The wind belts girdling the planet are organized into three cells in each hemisphere—the Hadley cell, the Ferrel cell, and the polar cell. Those cells exist in both the northern and southern hemispheres.

Longitudinal circulation (Walker circulation) – Latitudinal circulation is a result of the highest solar radiation per unit area (solar intensity) falling on the tropics. The solar intensity decreases as the latitude increases, reaching essentially zero at the poles. Longitudinal circulation, however, is a result of the heat capacity of water, its absorptivity, and its mixing. Water absorbs more heat than does the land, but its temperature does not rise as greatly as does the land. As a result, temperature variations on land are greater than on the water.

The Hadley Cell

- Solar heating at the equator is strongest, causing rising convective air which is pushed north and south at the tropopause (troposphere/stratosphere boundary).

- At ~30deg latitude it has deflected enough by the Coriolis force to be moving almost due east. Here, it meets air moving down from the north (Ferrel Cell air) and both meet and descend, warming and drying

- The return of the air, now a surface wind, to the equator is called the “trade winds”.

Mid-latitudes – The Ferrel Cell

- Convective rising air near 60 deg latitude arrives at the tropopause, moves (in part) to the south, deflecting by Coriolis to the west, till it meets the northerly moving air from the tropical Hadley cell, forcing both to descend

- These are the “Horse Latitudes” at +-30 deg latitude. Descending air dries. Deserts here (e.g. Sahara, Mojave/Sonora)

- Northerly moving surface winds deflected east – “the Westerlies” – carrying heat from the lower latitudes to higher mid-latitudes

- The primary circulation on Earth is driven by the equatorially heated Hadley Cell and the polar cooled Polar Cell. The Ferrel cell is a weaker intermediate zone, in which weather systems move through driven by the polar jet stream (the boundary between Ferrel and Polar cell, at the tropopause) and the tropical jet stream (the boundary between Ferrel and Hadley cells, at the tropopause).

- The jet streams have irregular paths as the convective instabilities migrate, and these drive the many cold and warm fronts which move through the Ferrel Cell.

The Polar Cell

- Easiest of the cells to understand – rising air from the 60-degree latitude area in part moves north to the pole, where it’s cold enough to densify, converge with other northerly winds from all longitudes, and descends.

- This makes a “desert” at the north and south poles.

Walker circulation

- The Southern Hemisphere has a horizontal air circulation cell called as Walker Cell responsible for upwelling along the South American Coast and bringing rains in Australia.

- The Walker circulation is the result of a difference in surface pressure and temperature over the western and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. A pressure gradient from east to the west creates an air circulation from the Eastern pacific (i.e. along the coast of Peru-Chile) to the western Pacific (Australia-New Guinea). This air circulation displaces surface water towards the western pacific causing cold water from beneath the ocean to move upward.

- Surface waters of the ocean are warm and the water under oceanic beds is cold and contains various types of nutrients that are helpful for aquatic life. Sea bird along the coast of South America (eastern pacific) gets plenty of Phytoplankton and produces Guano which again is helpful for Aquatic life. So, fishing is a thriving occupation along the eastern coast of South America.

- the western pacific and Australia receive precipitation due to Walker circulation.

- On the other hand, When the Trade Winds are weak, The warm water of the central Pacific Ocean slowly drifts towards the South American coast and replaces the cool Peruvian current. Such an appearance of warm water off the coast of Peru is known as El Nino.

- The El Nino event is closely associated with the pressure changes in the Central Pacific and Australia. This change in pressure conditions over the Pacific is known as the southern oscillation.

- The combined phenomenon of southern oscillation and El Nino is known as ENSO.

- In the years when the ENSO is strong, large-scale variations in weather occur over the world. The arid west coast of South America receives heavy rainfall, drought occurs in Australia, and sometimes in India, and floods in China. This phenomenon is closely monitored and is used for long-range forecasting in major parts of the world. (El-Nino in detail later)

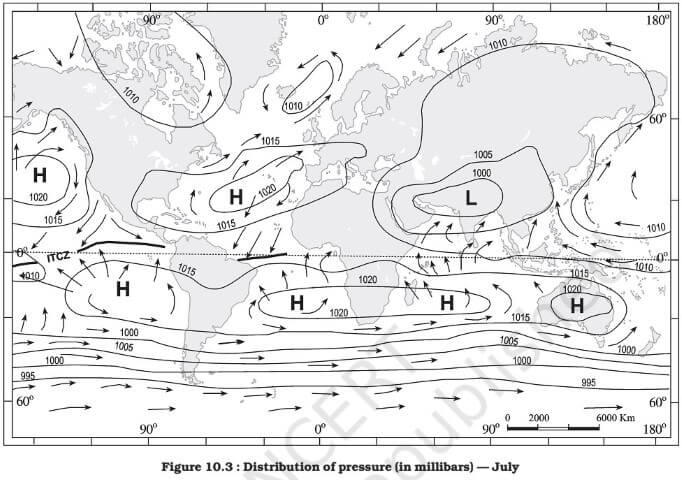

Pressure belts in July

- In the northern hemisphere, during summer, with the apparent northward shift of the sun, the thermal equator (belt of highest temperature) is located north of the geographical equator.

- The pressure belts shift slightly north of their annual average locations.

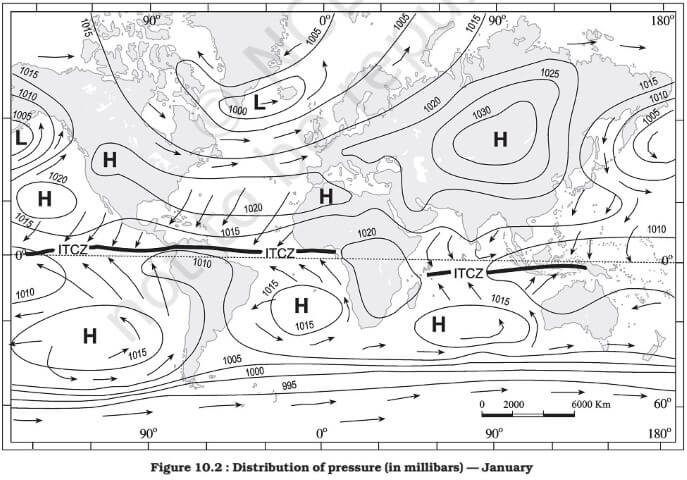

Pressure belts in January

- During winter, these conditions are completely reversed and the pressure belts shift south of their annual mean locations. Opposite conditions prevail in the southern hemisphere. The amount of shift is, however, less in the southern hemisphere due to the predominance of water.

- Similarly, the distribution of continents and oceans have a marked influence on the distribution of pressure. In winter, the continents are cooler than the oceans and tend to develop high-pressure centers, whereas, in summer, they are relatively warmer and develop low pressure. It is just the reverse with the oceans.

No comments:

Post a Comment